I have been reading Richard Dawkins'

The God Delusion (2006).

The reason that I have objected to the book previously is because he tars all religion with the same brush (as intolerant, irrational, imposing orthodoxy, and crushing all independent thought and opposition), and dismisses anything that doesn't resemble this picture as being "not really religion". From what I have read of the book so far, my criticism still stands.

It should be said at the outset that I

really don't believe in the God that Dawkins doesn't believe in. On pages 15 and 20, he says he is criticising "supernatural gods", in other words, ones that transcend nature, or are outside the universe. I don't believe in those. My theory is that what we call gods are personifications of places and phenomena - they are the names and personalities we give to that which is in Nature, part of Nature (immanent). By so doing, it is possible (by some hitherto unfathomed quantum weirdness) that we evoke consciousness in these things, or it could be that we are merely projecting it onto them. Nor do I believe that there is more than one level of reality; when Pagans and occultists talk about planes, we're not talking about spaces like geological strata, but modes of consciousness (Luhrmann, 1989: 276). I certainly don't believe in a Creator (some Pagans do, in the sense of some sort of consciousness that started the Big Bang) - I believe that consciousness is an emergent property of matter, and not the other way around.

But I don't believe that this invalidates the project of religion (at least not the way I and many others practice it). Religion is about reconnecting, to community, the universe, and reconnecting the parts of ourselves (bringing unconscious material into the light of consciousness, as Jung put it). I find "Einsteinian religion" (Dawkins, 2006: 20) very attractive, and also think that it bears a close resemblance to much of Paganism and Unitarianism. He also complains about people using "Einsteinian religion" to justify strong theism - well, fundamentalist Christians are very unlikely to use the views of universalists, pantheists and Pagans to justify their position, because they think we are all godless and immoral.

Right, so, on to the specifics. If I haven't mentioned a particular point, it means I agree with it, with the proviso that not all religion resembles the caricature of it depicted by Dawkins. Though there were some bits I agreed with so much that I just had to mention them.

Dawkins (2006: 1-2) asserts that a world without religion would be a world free of persecution. This is not necessarily the case, as there are many wars and conflicts caused by ethnic tension (e.g. the Hutu and the Tutsi in Rwanda). Alister McGrath, in

The Dawkins Delusion, spends a lot of pages refuting this suggestion, and points out that religious people also do a lot of good (caring for the sick, etc.)

I must wholeheartedly agree with Dawkins about the practice of indoctrinating children into their parents' religion, though. I think this practice is wrong and immoral and bad. Fortunately, the majority of Pagan parents agree with me. A Covenant of the Goddess poll in 2005 found that 49% of respondents indicated having no children, and of the remaining 51%, only 27% (i.e. approximately 13% of the

total sample) said that they were bringing their children up as Pagans. 52% of those with children said they were bringing them up in a multi-faith environment; 9% said 'another faith'; and 12% said 'none'.

On page 14, Dawkins states that he doesn't believe in a soul that outlasts the body. Well, Buddhists don't believe in the soul as a transcendent unity of consciousness and identity either; and nor do most Pagans - most Pagans believe in reincarnation as a transfer of some aspect of the self to a future incarnation, a "seed" of consciousness, if you like.

Most Pagans would also agree with the statement that there are no miracles except for natural phenomena; most Pagans would characterise the operations of magic as being part of Nature, manipulating the energy in things.

Dawkins also characterises 'pantheistic reverence' as non-belief -- well this is true if he means non-belief in the supernatural. But many Pagans object to the term supernatural, as we are deeply suspicious of claims to something existing beyond the universe.

On page 19, he says that using the term God in a metaphorical or pantheistic sense is wrong because most people mean 'supernatural creator' by the word. No, most Christians, Jews and Muslims mean 'supernatural creator' by the word. The creator in Hinduism, Brahma, may be a creator, but he is immanent, not transcendent (not supernatural). Pagans who do believe in a creator (or more likely creatrix, or in some cases, creators) don't tend to be that interested in worshipping it/him/her/them, regarding it as too big to be interacted with (because if it's immanent in the universe, the universe is an awfully big place, so it must be awfully big too). "Space is big, really big. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist's, but that's just peanuts to space." (Douglas Adams) Anyway, many Pagans refer to "deities" (

lots and lots of them) or to "The Goddess and the God" to indicate that they are not talking about God in any Abrahamic sense.

On page 26, he says that "any follower of any religion believes that theirs is the sole way, truth and light". That is simply not true. What about all the many people who participate in interfaith dialogue? What about the Unitarian Universalists, who explicitly say that all religions contain truth (and many of whom are non-theists). What about the Quakers, who say "

Be open to new light, wherever it may come from?" What about the Sufi universalists? What about the vast majority of Pagans?

On page 31, Dawkins states that "any creative intelligence of sufficient complexity to design anything, comes into existence only as the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution". I completely agree. But it doesn't rule out the emergence of consciousness as the product of complex systems other than ourselves.

On page 33, he states that Hindu polytheism is "really monotheism in disguise". This is true of some schools of Hinduism, but as Hinduism is non-creedal, there are many many paths within it, some of which are henotheistic, some of which are genuinely polytheistic, and some of which are monist (there is a monad of which the deities are emanations).

On page 34, he states that "theology has not moved on in 13 centuries". Really? What about John Scotus Eriugena, Spinoza, Teilhard de Chardin, A N Whitehead, Charles Hartshorne, Paul Tillich, Henri Bergson, feminist theologians (the Pagans among these are pantheistic), etc etc.

He also quotes Thomas Jefferson, but Jefferson was a deist (believed that the Divine was the first cause and then left the universe to itself). He also claims that Jefferson and others like him would have been atheists if they had lived in a more atheistic time. That seems like special pleading to me. How does he know what they would have believed?

On page 35, he asks, how did ancient pagans cope with polytheological conundrums (like is Thor the same as Thunor or Indra?) Who cares, asks Dawkins. Well, modern Pagans, that's who. There are some "hard" polytheists who are so vehemently non-monotheist that they will not even countenance Thor and Thunor being the same entity. Personally I think they are different cultural overlays on the same social interaction with a natural phenomenon.

On page 36, he dismisses feminist theology with "what is the difference between a non-existent female and a non-existent male?" Since many feminist theologians are pantheists (whom he graciously approves of) this seems unfair.

On page 37, he says that he is inclined to treat Buddhism and Confucianism as philosophical systems rather than religions. In this, he is simply falling into the trap of defining religion by what the West thinks it is, rather than as it actually practised by the rest of the world. Buddhism certainly has practices designed to further the process of enlightenment, which makes it a religion in my reckoning.

On page 46, he says that secularism is the only basis for interfaith harmony - I completely agree.

On page 47 and 48, he discusses the two types of agnosticism, PAP (Permanent Agnosticism in Principle) and TAP (Temporary Agnosticism in Practice). This is an interesting model, but I'm not quite sure where I fit within it. I think that there are some things that are unknowable (what happens to consciousness after death; what it's like to be another person; and what it is like to see from the perspective of the whole universe) and on these I am a PAP. I think there are other things which we do not know now which we one day will know (a scientific explanation for "magic"; whether or not string theory is true; etc.) and on these I am a TAP. Existence of the Divine? Not sure which category I would put that one in. If there is an underlying consciousness to the universe (in a pantheistic or animistic sense), then yes, I think it is possible for science to detect it - but maybe not the very materialist form of science we have now. I guess that makes me a TAP on this issue.

On page 50 he says that he suspects TH Huxley (who coined the word agnostic) was bending over backwards to concede a point. This is special pleading again. He may have been doing that, but unless he explicitly says so in the text, it is only a hypothesis.

Similarly, on page 57, he says that he simply does not believe that Stephen Jay Gould could have meant much of what he said in

Rocks of Ages. This is not a rational statement supported by evidence - it is simply a manifestation of Dawkins' prejudice. Why on earth did Gould publish the book unless he meant it (at least at the time; he might have changed his mind later)?

Another useful tool is the scale from theism to atheism on page 50 and 51. On this scale, I am at around 5 or 6 (Dawkins is a 7). But I still think religion is a useful tool for personal transformation, because the process of initiation in Paganism closely resembles the transformation of the psyche outlined in Jungian psychoanalysis.

On page 55, he discusses the concept of NOMA (the idea that religion and science are non-overlapping magisteria). The research I am currently conducting indicates that most Pagans do not agree with the NOMA view (nor does Dawkins).

He further says that science's entitlement to advise us on moral values is problematic; I'm glad he admits this (I'm thinking Oppenheimer here). He then suggests that we cut out the middle man in matters of morality. Quite so - this is precisely what non-creedal religions like Paganism and Unitarianism do. Most adherents of both these religions do not admit of any authority in matters of conscience beyond the self. (And I'm not about to start accepting Dawkins as either a moral authority, or an academic authority on the study of religion; he is far too blatant about having an agenda.)

He also says, well should we pick and choose among the world religions until we find a morality that suits us? No, he concludes. However, there is another possibility - that we use our discernment (an evolved emergent quality, to be sure) to triangulate between them, seeking out points where they agree and attempting to create a synthesis (but still not blindly accepting what they say unless it accords with reason, freedom and tolerance).

On page 58 and page 64, he quotes from a Richard Swinburne (a prominent Christian theologian, apparently). What R. Swinburne says to "explain" the Holocaust is thoroughly disgusting, and Dawkins rightly dismisses it as tosh. I can't believe this is the best that Christian theology has to offer as an explanation for suffering, though. If it is, they need to get some new theologians, and fast.

On page 59, he claims that religions rely on miracle stories to impress the faithful. Well, that's not true of all religions. Many spiritual traditions are based on the idea of personal transformation through various means. If they do not provide personal transformation, adherents lose interest and go elsewhere (but with most forms of Christianity, fear of damnation keeps them involved, which is a thoroughly immoral way to go about retaining members).

On page 60, he starts talking about prayer, but he is only talking about petitionary or intercessory prayer (asking for stuff). What about the type of prayer that is more like meditation or communing with the universe?

On page 67, he effectively declares war on religion, superstition and irrationality. Erm, isn't that a bit of an irrational response?

Not everything has to be rational. Love is irrational. Actually, the emotions and the reason need to work together in harmony. Too much emotion is bad, too much rationalism is bad. There's a great SF story called

The Cold Equations, where a little girl stows away on a spaceship, implying certain death for all on board if they don't push her out through the airlock. In the story, she ends up being pushed out through the airlock. It's one of those horrible ethical dilemmas that one hopes would never actually happen in real life - but it serves to show that reason by itself is cold and heartless.

On page 71, he mentions Jocelyn Bell Burnell, discoverer of quasars, but fails to mention that she is a Quaker. (I have no idea whether she is a theist or not, but she does practice a religion.)

On page 88, he discusses whether mystical experiences are all mad, psychotic and delusional. I think it depends on the nature and outcome of the experience. In the Preface, Dawkins says that he sometimes experiences a quasi-mystical oneness with the universe (and he knows that this is not delusional or psychotic). Well, lots of other people have this experience, and it's a wonderful experience. If it promotes greater compassion for others and wonder at the natural world, surely that is a good thing? If on the other hand, you hear voices telling you to go out and kill people, that's not a mystical experience, that is a psychotic delusion.

Dawkins (2006: 103-4) states that there have been 43 studies since 1927 on the relationship between intelligence and educational attainment and religious belief, and all but four found that the higher a person's intelligence and educational attainment, the less likely they were to have religious beliefs. Leaving aside the question of what is meant by intelligence and religious beliefs, my research findings would appear to imply that being more highly educated does not conflict with Pagan views, nor make them less likely (perhaps because Paganism is non-creedal). 69% of my respondents had attended higher education courses, and 29% of the subjects studied were scientific (archaeology, psychology, natural sciences, space sciences, earth sciences, life sciences, chemistry, physics, mathematics, computer sciences, and engineering). Of course, this may be because the sample was self-selecting and not randomly selected; perhaps the more highly-educated would worry more about the compatibility of their Pagan views with science, and thereby be drawn to the questionnaire. Nevertheless, other researchers have noted the predominance of middle class people in Paganism (Luhrmann, 1989: 29; Adler, 1986: 449) and several studies have noted that Pagans are voracious readers, regardless of educational level (Clifton, 2006: 13).

On page 104, he discusses Pascal's Wager, the idea that you might as well believe in God, because if you do and it all turns out to be true, then you'll go to Heaven, and if it's not true it won't have done you any harm; whereas if you don't and it turns out to be true, you'll go to hell. Dawkins very effectively demolishes this horrible and disgusting idea, except that he forgot to say that a God who sent people to hell for not believing in it would be thoroughly immoral, vindictive, and horrible (and Eastern Orthodox theologians have made the same point).

On page 107, he discusses the word "faith" (by which he means blind faith). Most Pagans are very uncomfortable with the word "faith". I regard my "beliefs" as working hypotheses to explain my experience, and so do 38% of the respondents to my questionnaire on Pagans and science.

That's as far as I have got at present. I will write more when I have read more of the book.

To sum up, I agree with his dismissal of the supernatural; I think that "spirits" and "magic" are properties of nature in the same way as consciousness is. I do not agree that religion is about "worshipping a supernatural creator". Pagans revere the divine in Nature. 65% of my sample agreed that deities and other spirits have developed out of our social and ritual interaction with place and space, and 72% agreed that the divine is (or deities are) immanent in the universe. 20% were neutral on this issue. (The ones who didn't agree that the divine was immanent in Nature were also the ones who didn't believe in the divine.)

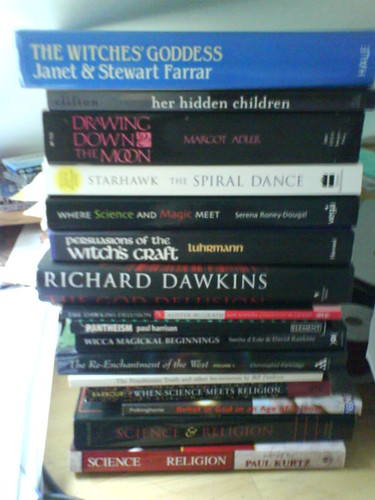

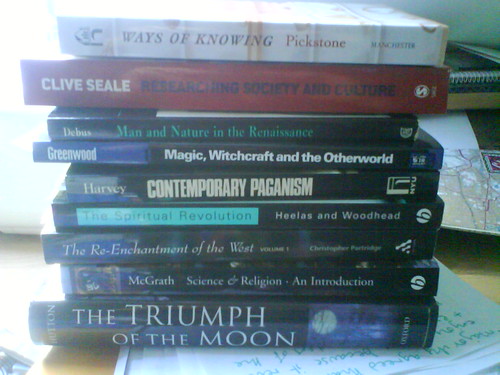

Bibliography

Adler, M. (1986) Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston: Beacon Press.

Clifton, C. (2006). Her Hidden Children: The Rise of Wicca and Paganism in America. New York: Altamira Press.

Dawkins, R. (2006) The God Delusion. London: Bantam Press.

Luhrmann, T. (1989) Persuasions of the Witch's Craft: Ritual Magic in Contemporary England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[Part 2 of A Pagan response to Dawkins]